The Dusenberry Collection

When Harold Lyle Dusenberry (1907-1991) visited Nepal for the first time in 1951, as a Technical Advisor at USOM (US Operations Mission, later to be called USAID) Nepal had just signed the Point IV Agreement with the United States of America, for cooperation in Rural Development. Back then the Rana regime had just ended and Nepal was a fledgling nation trying to come to terms with the rest of the world, from which it had been isolated for centuries. Sixty years since then, Nepal is still a fledgling nation in many ways, however much has changed, and the Dusenberry Collection of black and white photographs at Madan Puraskar Pustakalaya (MPP) provides a testimony to that. The collection came to MPP through Mr Prakash Mani Dixit –currrently in the United States- back then a young officer with USOM and a colleague of Mr. Dusenberry

Going by the collection of photographs, some 500 of them, Dusenberry appears to have been a person interested in just about everything in Nepal. He took photographs of monuments and landscapes of Kathmandu, which can be said as nothing uncommon for a foreigner. Also, being a foreigner hobnobbing with the royalties and the elite must also have been a fairly common phenomenon. These American advisors, Mr Dixit in a brief note introducing the photograph collection writes, ‘got the opportunity to work with a wide array of populations, from kings to peasants, businessmen to religious leaders, and politicians to the general public’. His photographs also reflect this, for instance, there are photographs of kings and crown prince, prime ministers and foreign envoys; politicians of the newly liberated Nepal and of the glamour still extant inside the royal courts. There are also some images that capturing the occasional cultural activities, like construction of the chariot of Rato Machhindranath, a wedding etc. However, these ‘regular’ sorts of photographs are not the principal reason the Dusenberry collection is unique. Its exclusivity lies in the photos that are not regular.

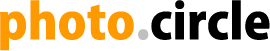

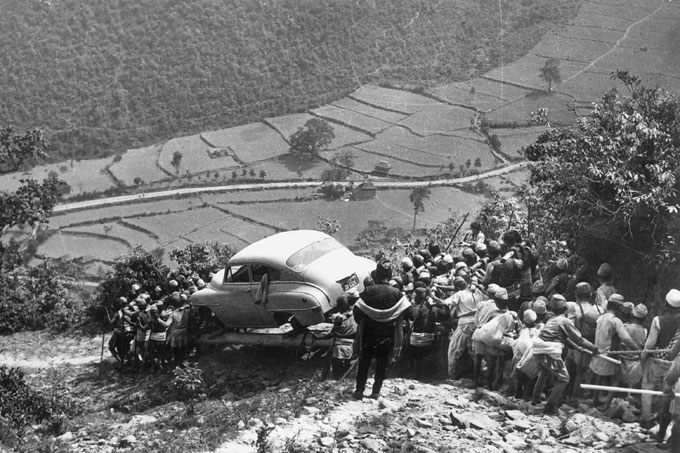

Dusenberry was an agriculturist, and some photographs of his collection document the then agricultural scenario, farmers, farming techniques, farming tools etc. Until 1951, Nepali farmers relied totally on traditional agricultural practices. For instance in Kathmandu, clay soil was used as fertilizers and several farmers lost their lives, or were handicapped every year digging out clay from perilous pits. The collection is an important documentation, valuable for understanding the history of modern agriculture in Nepal. His job also took Dusenberry outside Kathmandu valley, as evident from photographs from the mofussil. Places like Pokhara, Birgunj, Narayanghat barely recognizable from their present states, also find their presence in the collection.

All these fascinating moments of a newly opened Nepal, are still available, thanks to Harold Lyle Dusenberry and Prakash Mani who understood the value of his work and contributed his collection to MPP

With a collection of around 15,000 rare black and white and 35,000 new images, MPP has been working to raise awareness about the relevance of photo archives. There is urgency to make the public understand the value of conserving photographs, as the images that represent personal moments and events in our lives today, will be important historical material tomorrow. For instance, an image casually clicked of the street outside one’s house can become a crucial tool to understand the landscape and architectural history of that area, let’s say 50 years down the line. Importance of photo archives can not be overstated. They are much sought for by historians, sociologists, anthropologists, and scholars belonging to a wide array of disciplines. In a country where there is no national photo archive, it is even more important to preserve those frozen moments of history.

Much changed in the six years Dusenberry worked in Nepal, first from 1951- 1955 and second from 1958-1960. Nothing would remain the same, for good or for worse, not only in politics but also in agricultural practices. By the end of the 50s Nepali farmers had begun to use chemical fertilizer; scores of people were trained in modern agricultural practices, animal husbandry and agricultural tools. That world, in terms of its physical existence, is lost for ever. Courtesy the old images, we can still take a peek into that world time and again, through the frames of Mr. Dusenberry and few others like him.

For details, visit Madan Puraskar Pustakalaya.